Warming spring weather is stimulating new growth among vegetation that was dormant or shabby through this winter.

1. Rosa spp., rose started growing even before the weather became warmer. It is good to see that squirrels are not eating the new growth. I do not know what cultivar this one is.

2. Hydrangea macrophylla, hydrangea, which is also unidentified, also started growing while the weather was still cool and rainy. It is now settling in after bare root relocation.

3. Nephrolepis cordifolia, sword fern, like many ferns, is beginning to replace old foliage with new foliage. It grew too large for its pot years ago, but somehow continues to grow.

4. Clivia miniata, Kaffir lily has been maturing slowly for more than a year, but is finally providing a pup. It is variegated with yellow stripes, but I do not know what cultivar it is.

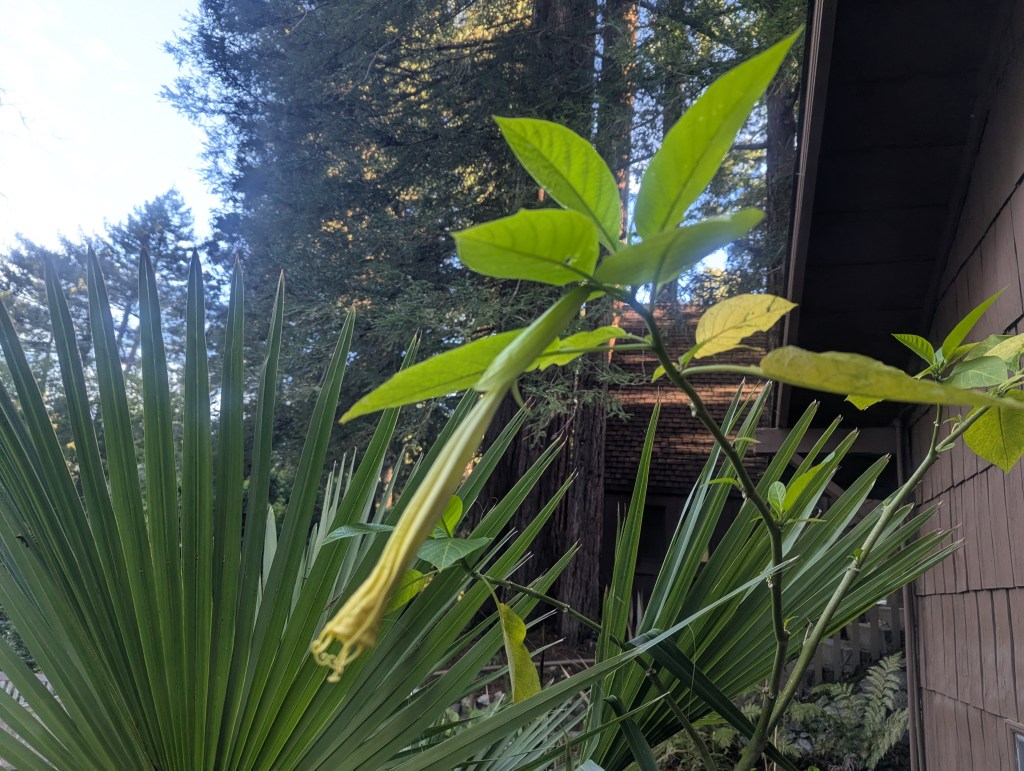

5. Brugmansia X cubensis ‘Charles Grimaldi’ angel’s trumpet is producing a new flower as readily as it produces new foliage. It should be no surprise. it is rarely without bloom.

6. Musa acuminata X balbisiana ‘Golden Rhino Horn’ banana starts to produce its new foliage about the time we consider taking it out of the landscape because it is so shabby.

This is the link for Six on Saturday, for anyone else who would like to participate: https://thepropagatorblog.wordpress.com/2017/09/18/six-on-saturday-a-participant-guide/