Sunday Best – Spanish Lavender

The first is Spanish. The second is Chinese. The rest, including Oregon grape, are native. Only the iris and poppy were actually found growing in the wild, though. It is beginning to look like spring.

1. Lavandula stoechas, Spanish lavender compensates for its absence of floral fragrance with delightful foliar aroma, especially as the weather begins to get warmer after winter.

2. Loropetalum chinense, Chinese fringe flower blooms with these silly rosy pink flowers above lightly bronzed new foliage, which is collectively more colorful than simple bloom.

3. Ribes sanguineum, flowering red currant, although native here, does not grow wild in this particular location. This one was added to one of the landscapes, and is quite happy.

4. Iris fernaldii, Fernald’s iris does grow wild here, and seems to bloom more happily on exposed roadsides than in forests. Perhaps it appreciates the better exposure to sunlight.

5. Mahonia aquifolium, Oregon grape is the Official State Flower of Oregon. It is native, but was likely added to the several landscapes that it inhabits here, like the red currants.

6. Escholzia californica, California poppy is the Official State Flower of California. It can be a bit prolific in some situations, while less prolific where seed are intentionally sown.

This is the link for Six on Saturday, for anyone else who would like to participate: https://thepropagatorblog.wordpress.com/2017/09/18/six-on-saturday-a-participant-guide/

Not much can survive in the shade of broad eaves that extend over a northern exposure. With sufficient watering, that is where the leopard plant, Farfugium japonicum, can excel. It is naturally an understory species that prefers the shade of bigger vegetation. If it does not get too dry, it also performs well with full sun exposure. It enjoys organically rich soil.

Leopard plant is a striking foliar plant, but may also bloom for autumn or winter. Its bright yellow daisy flowers are about an inch wide, and bloom in loose trusses. The glossy and evergreen foliage might be foot and a half high. Some cultivars are more compact, while old cultivars may get slightly bigger. Individual leaves are about three to six inches wide.

Popular cultivars of leopard plant are notably diverse. Most are variegated with yellow or white spots, blotches, margins or irregular streaks. Some exhibit wavy, crinkly or convex foliar margins. Yet, the most popular is likely the old fashioned cultivar with simple, deep green foliage. Their subterranean rhizomes migrate, but rather slowly. Too much fertilizer can cause foliar burn or even inhibit bloom.

Climates are regionally prevalent patterns of weather. The climate here is a chaparral or Mediterranean climate. It is characterized by warm and arid summers, and mild and rainy winters. Many adjacent climates are similar, even if slightly different. Coastal, alpine and desert climates occur elsewhere in California. Microclimates occur within such climates.

The climates of California are as diverse as the geology that influences them. Mountains and valleys and everything in between develops its distinct climate. Some counties here include more climates than some individual states. Many climate zones are impressively compact. So much diversity with small climate zones is often mistaken for microclimates.

Microclimates are small climates within bigger climates. This is obvious. However, there is no definitive description of how small they are. Climates generally conform to geology, like elevation, latitude and proximity of oceans. Microclimates generally conform to what is on such geology, like forests or pavement. They can fit within compact home gardens.

Roofs and pavement of urban areas absorb and radiate significant heat. Such heat alters associated microclimates. Conversely, urban trees and vegetation might cool associated microclimates. Home gardens that are near freeways may be slightly warmer than those that are not. Well forested neighborhoods are a bit cooler during warm summer weather.

These are large scale examples, though. Microclimates originate within individual home gardens also. Southern exposures are much sunnier and warmer or hotter than northern exposures. Eastern exposures are as sunny as western exposures, but are not as warm. Eaves might shelter vulnerable vegetation from mild frost, but also exclude rain moisture.

Microclimates can change as gardens evolve. Shade trees grow to produce more shade. Taller fences may replace shorter fences. Painting a home a different color changes how it reflects or absorbs sunlight. Awareness of microclimates facilitates selection of species for each particular situation. It also facilitates selection of situations for particular species.

Warming spring weather is stimulating new growth among vegetation that was dormant or shabby through this winter.

1. Rosa spp., rose started growing even before the weather became warmer. It is good to see that squirrels are not eating the new growth. I do not know what cultivar this one is.

2. Hydrangea macrophylla, hydrangea, which is also unidentified, also started growing while the weather was still cool and rainy. It is now settling in after bare root relocation.

3. Nephrolepis cordifolia, sword fern, like many ferns, is beginning to replace old foliage with new foliage. It grew too large for its pot years ago, but somehow continues to grow.

4. Clivia miniata, Kaffir lily has been maturing slowly for more than a year, but is finally providing a pup. It is variegated with yellow stripes, but I do not know what cultivar it is.

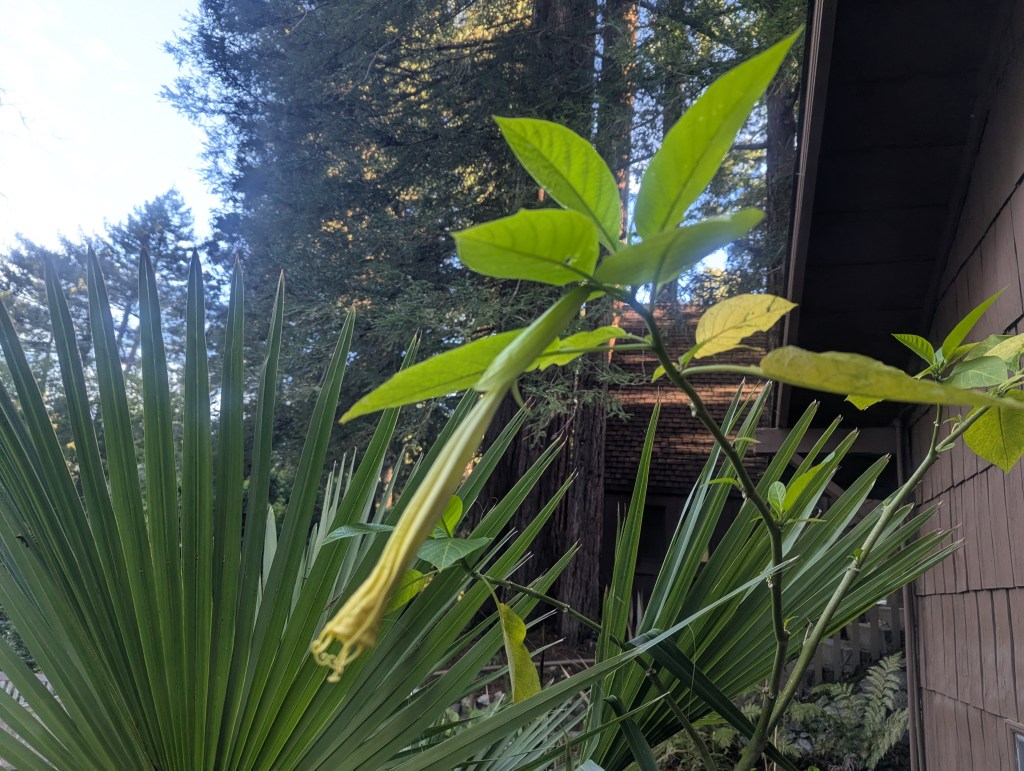

5. Brugmansia X cubensis ‘Charles Grimaldi’ angel’s trumpet is producing a new flower as readily as it produces new foliage. It should be no surprise. it is rarely without bloom.

6. Musa acuminata X balbisiana ‘Golden Rhino Horn’ banana starts to produce its new foliage about the time we consider taking it out of the landscape because it is so shabby.

This is the link for Six on Saturday, for anyone else who would like to participate: https://thepropagatorblog.wordpress.com/2017/09/18/six-on-saturday-a-participant-guide/

Like most warm season vegetables, tomatoes, Solanum lycopersicum, are actually fruits. They contain seed, whereas actual vegetables are vegetative plant parts that lack seed. Although mostly red, some are orange, yellow, green, pink, brown, purple or pallid white. Some are smaller than small grapes, while ‘Beefsteak’ may grow wider than five inches.

For home gardens, the most popular varieties of tomato are indeterminate. They produce their fruit sporadically throughout their season, on lanky irregular stems. They are neater with the support of tomato cages or stakes. Determinate varieties are shrubbier and more productive, but only for a brief season. They are quite conducive to succession planting.

It is still a bit too early for small tomato plants to go into their gardens. However, seed can start inside or in a greenhouse now. It is possible to sow seed directly into a garden later, but they are vulnerable to mollusks. Nurseries can stock several varieties of tomatoes as small plants. Countless more varieties are available from mail order or online purchases. Many heirloom varieties truly are strange and unique.

Warm season annuals know what time it is. Although it is still too early for many to move directly into gardens, a few already are. A few can start from seed, either in greenhouses or directly in their gardens. Eventually, as the weather warms, they all can live outside for the summer. Warm season vegetables, or summer vegetables, are in the same situation.

After all, almost all warm season vegetables perform as annuals. The weather is still too cool for seedlings to go out into their gardens. However, it is time to start some vegetable plants from seed. Some should start inside or in a greenhouse. Others might start directly in their gardens. The weather should be warm enough for them by the time they develop.

Seed for most root vegetables can go directly into their gardens now. Root vegetables do not recover from transplanting easily, so prefer direct sowing. Transplanted seedlings are susceptible to root disfigurement. Corn, squash and beans prefer direct sowing also, but should wait for warmer weather. Seedlings grow faster than the weather becomes warm.

Tomato and pepper plants prefer to go into the garden later as seedlings or small plants. Such small plants will become available from nurseries as they become more seasonal. Alternatively, they can start to grow from seed inside or in a greenhouse now. Their fresh seedlings should be ready for their garden as the weather warms. Scheduling is crucial.

The advantages to seed are that it is less expensive and more diverse than small plants. Packets of seed cost about as much as six packs of small plants, but contain many seed. Nurseries stock only a few varieties of each type of vegetable plant. However, they stock a few more varieties of seed for the same type of vegetables. Many are available online.

Cucumber, eggplant and melon can grow either from small plants or directly sown seed. A single small plant may be more practical for melon because only one plant is sufficient. However, if several cucumber plants are preferable, seed may be more practical. If seed are preferable, they can start soon. Small plants might wait a bit longer after the last frost.

After several weeks of atypically warm and pleasant weather, more typical cool and rainy weather resumed to demonstrate that winter is not quite finished yet.

1. Brugmansia suaveolens, angel’s trumpet becomes rather scrawny through winter as it sheds its larger leaves that grew through summer, and generates smaller leaves instead.

2. Musa acuminata X balbisiana ‘Blue Java’ banana would be notably scrawnier than it already is if more of its discolored and weather damaged foliage were to be pruned away.

3. Viola X wittrockiana, pansy is a cool season or winter annual, but even it craves a bit more warmth than it has been experiencing since it was planted two or three weeks ago.

4. Canna X generalis, canna of various cultivars got cut back as their foliage succumbed to wintery chill and wind, but are already growing fast to replace what was pruned away.

5. Alocasia macrorrhizos, taro was divided just before the weather got cool again, so it is difficult to know if it wilted because of the division, the lack of warmer weather, or both.

6. Philodendron selloum ‘Lickety Split’ split leaf philodendron was divided immediately after the taro, but has not wilted, and seems to be more resilient to the wintery weather.

This is the link for Six on Saturday, for anyone else who would like to participate: https://thepropagatorblog.wordpress.com/2017/09/18/six-on-saturday-a-participant-guide/