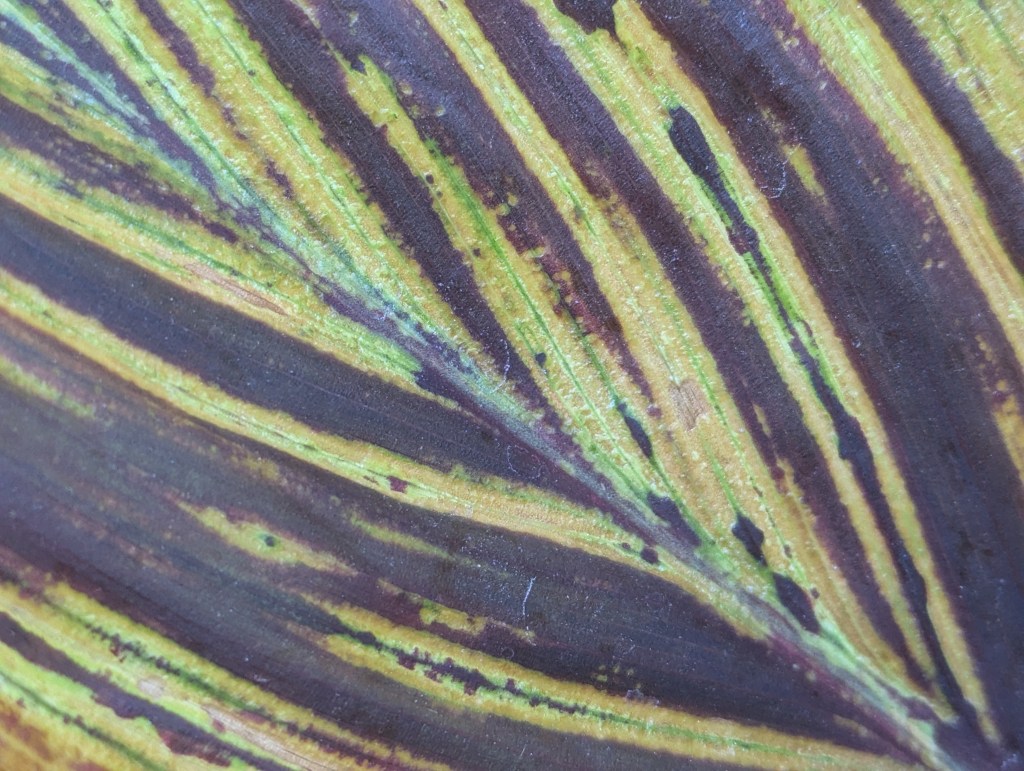

This is not a new problem, but it is infuriating nonetheless. ‘Cleopatra’ canna expressed symptoms of at least one virus about two years ago. A few other nearby cannas expressed similar symptoms shortly afterward. ‘Australia’ canna is particularly expressive of foliar streaking caused by virus. Isolation and disposal of obviously infected specimens seems to have prevented dispersion of the virus or viruses; but I really am uncertain. Three cultivars of Canna musifolia have suspiciously avoided any infection from adjacent infected cultivars. I can not help but wonder if they are actually infected but merely asymptomatic, and possibly able to transmit viruses to cultivars that are more expressive of symptoms. The canna in this picture is an important cultivar because it is one of only two remaining original cultivars that could have inhabited the landscapes here since about 1968. Because of gophers, very little of it remain, and some of what remains succumbed to virus already. I am quite protective of these few specimens that have not been infected, but would also like them to be able to inhabit the landscapes with the questionable Canna musifolia cultivars. For now, I must wait until they proliferate enough for some to be expendable.

It is not easy for wild trees to adapt to a refined landscape. After a lifetime of adapting to their native environment and dispersing their roots to where the moisture is through the dry summers, they must adapt to all sorts of modifications such as excavation, irrigation and soil amendment. Newly installed plants grow into a new landscape while some mature trees succumb to disease and rot.

It is not easy for wild trees to adapt to a refined landscape. After a lifetime of adapting to their native environment and dispersing their roots to where the moisture is through the dry summers, they must adapt to all sorts of modifications such as excavation, irrigation and soil amendment. Newly installed plants grow into a new landscape while some mature trees succumb to disease and rot.