Propagation produces more plants from minimal and readily available resources. Within home gardens, propagation is practical by seed, cutting, layering or division. Seed which is not available directly from the garden is generally not very expensive. Cutting, layering and division utilize what already lives within the garden. In other words, the stock is free.

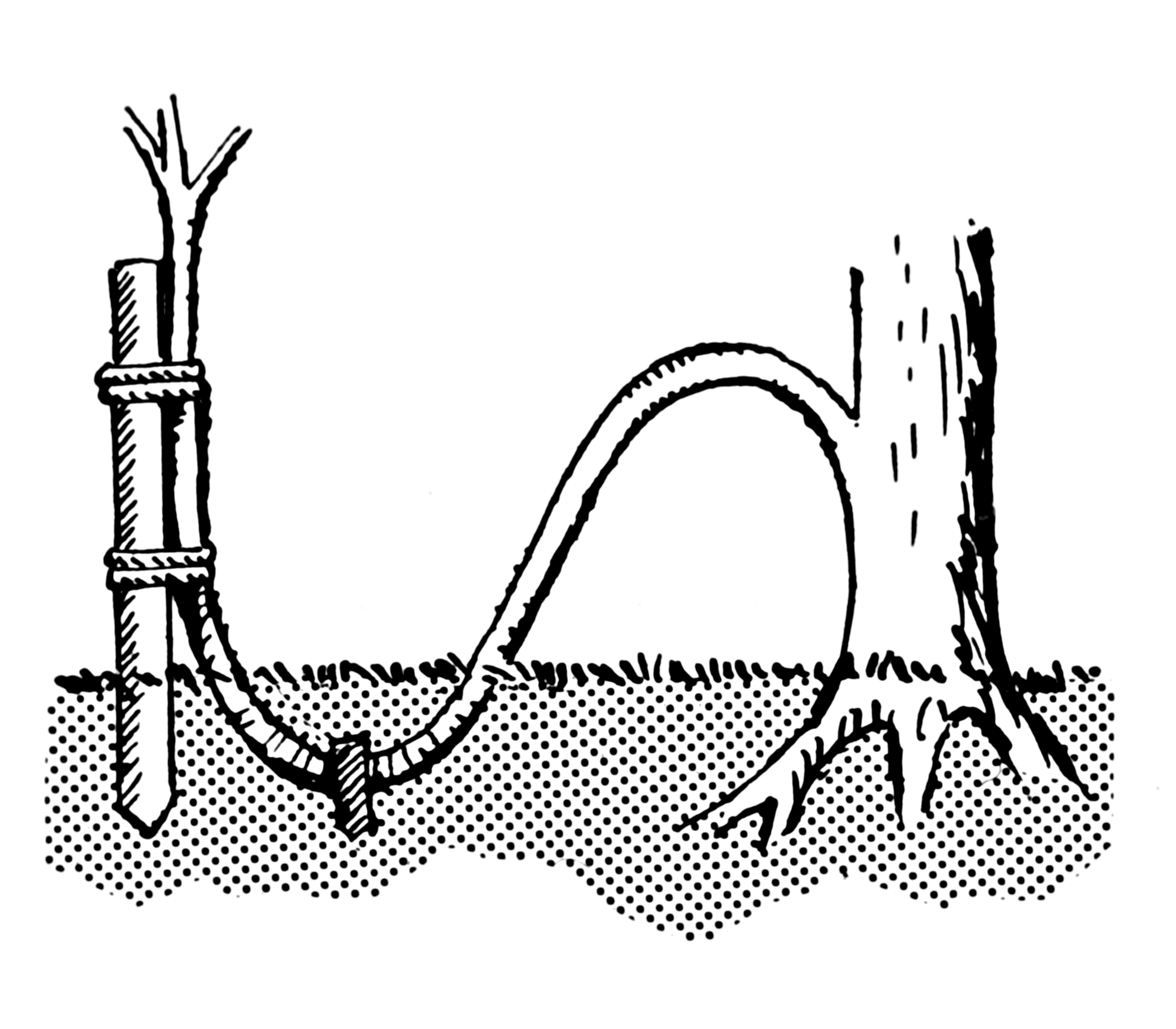

Seeding produces genuinely new plants. Other forms of propagation produce genetically identical copies of their parent plants. Cutting compels pieces of stem to grow new roots. Layering does the same, but while pieces of stem remain attached to their parent plants. Division involves separation of portions of stems that already developed their own roots.

Most species that are conducive to division are substantial perennials. Flowering quince and lilac, though, are woody shrubs that produce dividable suckers. Most division should happen during late summer or early autumn. However, several species prefer late winter. Deciduous species, like lilac and flowering quince, prefer it during their winter dormancy.

Shasta daisy, lily of the Nile, daylily and coneflower prefer division during late summer. It is after their bloom and summer warmth, but before cool weather of winter. They disperse their roots through winter to resume growth even before spring. Bearded iris are ready for division a bit earlier, and resume growth by autumn. They are then ready for early spring.

Division of phlox and penstemon should be a bit later, when they get cut back. Bergenia blooms for winter, so should not be disturbed until late winter. Torch lily might bloom late, so also prefers to wait until late winter. New Zealand flax recovers from the process more efficiently after winter. It grows slowly during wintry weather, so is more susceptible to rot.

Daylily is easy to divide by simply digging and separating foliar rosettes from each other. Lily of the Nile is as simple but more work because of tough roots. Shasta daisy involves cutting apart clumps of its matted basal stems. Each clump, which may be cut away with a shovel, contains several such stems. Newly divided plants might bloom better because they are not quite so crowded.

All plants propagate. Otherwise, they would go extinct. They all have the potential to propagate by seed or spores. However, some are more efficient at vegetative propagation from stems or roots. Of the later, a few propagate by seed so rarely that it is a wonder that they can evolve, since vegetatively propagated plants are clones, or genetically identical copies, of the original plants.

All plants propagate. Otherwise, they would go extinct. They all have the potential to propagate by seed or spores. However, some are more efficient at vegetative propagation from stems or roots. Of the later, a few propagate by seed so rarely that it is a wonder that they can evolve, since vegetatively propagated plants are clones, or genetically identical copies, of the original plants.