Molluscs, rodents, insects, virus, fungal pathogens and an identified disease that causes gummosis; we have it all. I know that it is nothing to brag about, but it makes a good six.

1. Tamarindus indica, tamarind seedlings are popular with slugs. Not much else here is. Weirdly, slugs do not seem to consume the foliage. They only coat it with slime that does not rinse off. The foliage eventually deteriorates. What is the point of this odd behavior?

2. Prunus armeniaca, apricot trees sometimes exude gummosis as a symptom of disease or boring insect infestation. I can not see what caused this, and do not care to. I will just prune it out. I know that it will not be the last time. Gummosis is common with apricots.

3. Chamaedorea plumosa, baby queen palm was chewed so badly by some sort of rodent that it will not likely survive. I suspect that a squirrel did this. I have not seen any rats or their damage since Heather arrived. This is one of only two rare baby queen palms here.

4. Ensete ventricosum ‘Maurelii’ red Abyssinian banana was initially infested with aphid and associated mold. The aphid disappeared, as it typically does, but the mold remained and ruined the currently emerging leaf. I hope that the primary bud within does not rot.

5. Passiflora racemosa, red passion flower vine has been defoliated a few times just this year by a few of these unidentified caterpillars. The caterpillars leave after they consume all foliage, but then return shortly after the foliage regenerates, while I am not watching.

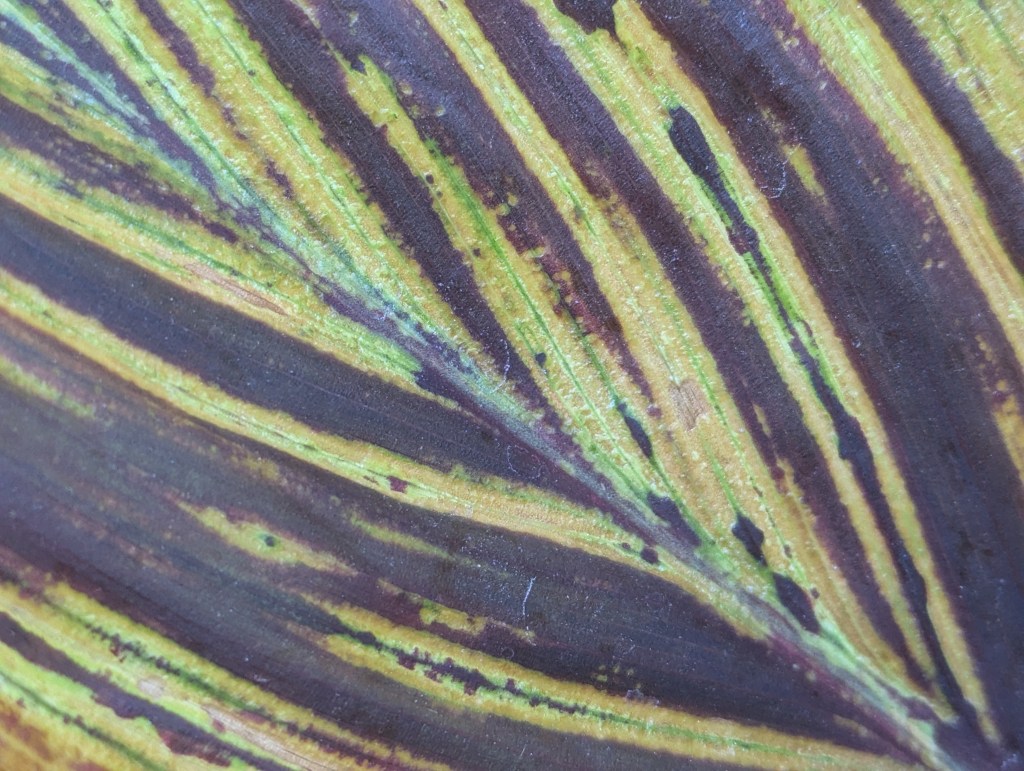

6. Canna indica ‘Australia’ canna is infected with canna mosaic virus. Several others are also, although they do not express symptoms as colorfully as ‘Australia’ does. Most other cannas are isolated from this virus within their landscapes. I am infuriated nonetheless.

This is the link for Six on Saturday, for anyone else who would like to participate: https://thepropagatorblog.wordpress.com/2017/09/18/six-on-saturday-a-participant-guide/