Those who know trees mostly agree that the more traditional catalpa, Catalpa speciosa, from the Midwest is the best catalpa, with soft leaves between half and a full foot long. In late spring or early summer, impressive upright trusses suspend an abundance of bright white, tubular flowers with yellow or tan stripes and spots at their centers. Individual flowers are as wide as two inches. Mature trees can be taller than forty feet and nearly as broad.

From the Southeast, Catalpa bignonioides, is a bit more proportionate to urban gardens though, since it only gets about seventy five percent as large, with leaves that are not much more than half as long. The flowers are also smaller, and not quite as bright white, but are more abundant than those of Catalpa speciosa are. The stripes and spots at their centers are slightly more colorful purplish brown and darker yellow.

Both catalpas can be messy as their flowers fall after bloom. Fortunately, the big leaves are easy to rake when they fall in autumn. Long seed capsules that look like big beans linger on bare trees through winter.

Catalpa speciosa is almost never seen in modern landscapes, and not exactly common even in older Victorian landscapes around downtown San Jose. A few remarkable specimens remain as street trees in older neighborhoods of Oakland, Burlingame and Palo Alto. Most young trees were not planted, but instead grew from seed from older trees that are now gone.

Catalpa bignonioides is actually quite rare locally. A few old but healthy specimens can be seen around downtown Felton, with a few younger trees that grew from seed around the edges of town. Trees in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco are not as happy because of cool and breezy summers and mild winters.

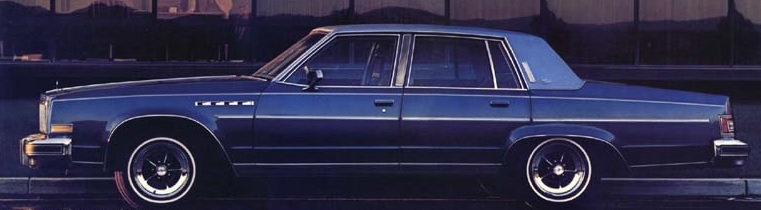

For my exquisite 1979 Electra, planned obsolescence did not work out so well. It was probably a grand Buick for that time, and one of the last with tail fins! It was elegant. It was big. It was steel. It was made to last ten years or 100,000 miles . . . and that was it. Seriously, as much as I enjoyed that car, it did not want go to much farther than it was designed to go. It limped along for almost 20,000 miles more, but was not happy about it, and was really tired and worn out by the time it went to Buick Heaven.

For my exquisite 1979 Electra, planned obsolescence did not work out so well. It was probably a grand Buick for that time, and one of the last with tail fins! It was elegant. It was big. It was steel. It was made to last ten years or 100,000 miles . . . and that was it. Seriously, as much as I enjoyed that car, it did not want go to much farther than it was designed to go. It limped along for almost 20,000 miles more, but was not happy about it, and was really tired and worn out by the time it went to Buick Heaven.