Shrubbery behaving badly can be a problem. Many seemingly innocuous shrubs get planted in situations where they do not fit, and soon get too big for the space available. Others do not get shorn or pruned as they should, or simply get neglected, and eventually get overgrown. Many others have sneaky ways of sowing their seeds in awkward places where they would not otherwise get planted by anyone who knows better.

Most home improvement shows on television would simply recommend removing obtrusive, overgrown or inappropriate shrubbery and replacing it with something more proportionate, appropriate and stylish. What a waste! Hidden within overgrown shrubbery, there are sometimes potentially appealing small trees that only need to be released from thickets of overgrowth.

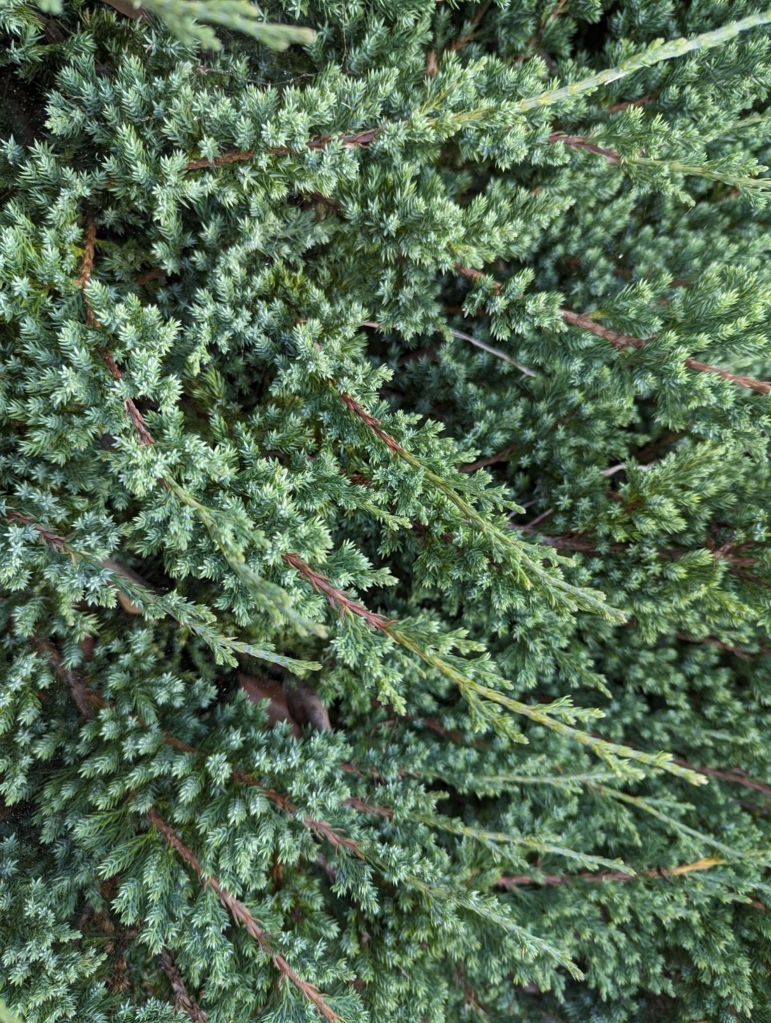

Overgrown Australian tea tree, sweet olive (Osmanthus fragrans), xylosma, glossy privet, ‘Majestic Beauty’ Indian hawthorn, and larger types of oleander, holly, pittosporum, cotoneaster and juniper are often easily salvaged by aggressive selective pruning rather than indiscriminate pruning for confinement. Lower growth that has become obtrusive, disfigured or otherwise unappealing can be thinned or removed to expose substantial sculptural trunks within. Upper growth that is out of the way can be left intact or thinned as necessary, but should not shorn or pruned indiscriminately. This creates informal small trees with distinctive trunks from what had been overgrown shrubbery.

Some shrubbery may need some time to grow out of its former confinement, and may be somewhat unsightly during the process. As they develop though, they should require less maintenance, since most of their growth should be up out of the way instead of where it is in constant need of pruning for confinement.

Many small trees that often get shorn into shrubbery would similarly do better with selective pruning to enhance natural branch structure and eliminate congested thicket growth. Japanese maples, redbuds, smoke tree, English hawthorn, crape myrtle, parrotia, loquat, strawberry tree, Pittosporum undulatum, and small types of magnolias, acacias, and yew pines (Podocarpus spp.) are notorious for getting shorn into unmanageable shrubbery. Pineapple guava, photinia, toyon, hop bush, larger types of bottlebrush and smaller types of melaleucas are more conducive to being shorn and pruned as large shrubbery, or can be pruned into small trees if preferred.