Sunday Best – 4:00

Molluscs, rodents, insects, virus, fungal pathogens and an identified disease that causes gummosis; we have it all. I know that it is nothing to brag about, but it makes a good six.

1. Tamarindus indica, tamarind seedlings are popular with slugs. Not much else here is. Weirdly, slugs do not seem to consume the foliage. They only coat it with slime that does not rinse off. The foliage eventually deteriorates. What is the point of this odd behavior?

2. Prunus armeniaca, apricot trees sometimes exude gummosis as a symptom of disease or boring insect infestation. I can not see what caused this, and do not care to. I will just prune it out. I know that it will not be the last time. Gummosis is common with apricots.

3. Chamaedorea plumosa, baby queen palm was chewed so badly by some sort of rodent that it will not likely survive. I suspect that a squirrel did this. I have not seen any rats or their damage since Heather arrived. This is one of only two rare baby queen palms here.

4. Ensete ventricosum ‘Maurelii’ red Abyssinian banana was initially infested with aphid and associated mold. The aphid disappeared, as it typically does, but the mold remained and ruined the currently emerging leaf. I hope that the primary bud within does not rot.

5. Passiflora racemosa, red passion flower vine has been defoliated a few times just this year by a few of these unidentified caterpillars. The caterpillars leave after they consume all foliage, but then return shortly after the foliage regenerates, while I am not watching.

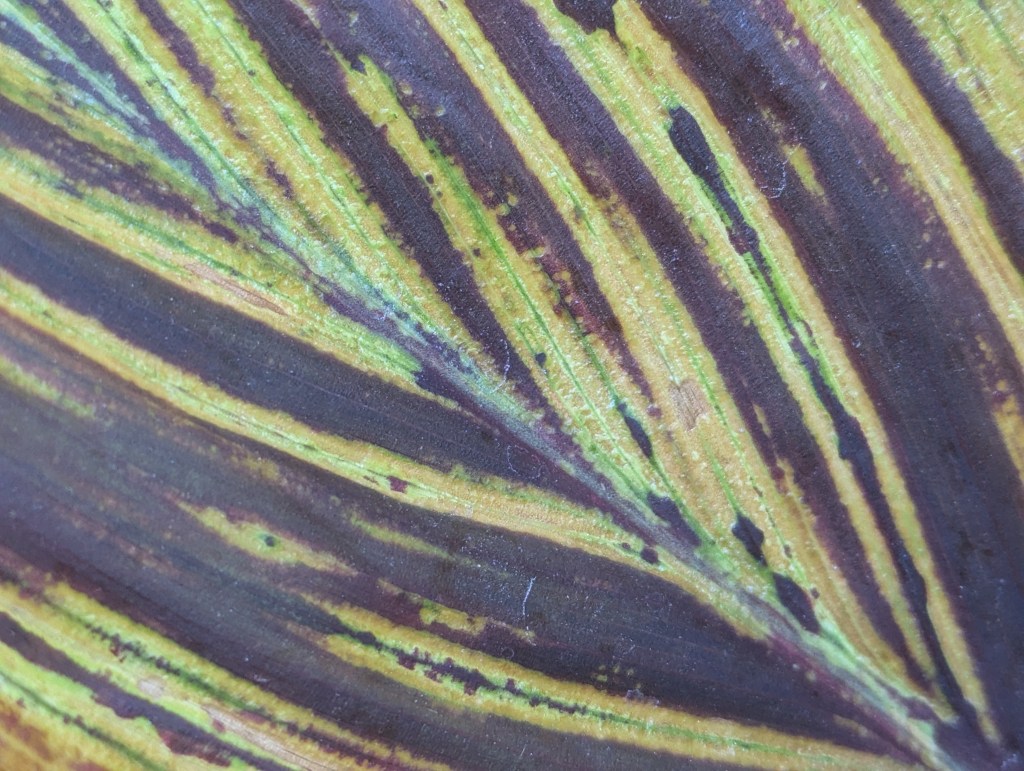

6. Canna indica ‘Australia’ canna is infected with canna mosaic virus. Several others are also, although they do not express symptoms as colorfully as ‘Australia’ does. Most other cannas are isolated from this virus within their landscapes. I am infuriated nonetheless.

This is the link for Six on Saturday, for anyone else who would like to participate: https://thepropagatorblog.wordpress.com/2017/09/18/six-on-saturday-a-participant-guide/

Where it grows wild in the eastern half of North America, honey locust, Gleditsia triacanthos, may not seem like it would be such an appealing shade tree. It is too thorny and messy to make many friends. As it matures and grows nearly seventy feet tall and half as broad, the thorny stems stay overhead and out of the way. However, a larger canopy makes more messy and sometimes unsightly foot long seed pods.

Modern cultivars of the thornless form Gleditsia triacanthos inermis are friendlier and not so messy. Mature trees only grow about half as tall as wild trees. Their main problem is their buttressing roots, which can displace pavement, but stay tolerably low for lawns. Honey locust is actually a good shade tree for lawns (if minor buttressing is not a problem) because it makes just enough shade without getting too dark for a lawn or other shade tolerant plants below. Pods are rare.

The big eight inch long leaves are bipinnately compound, which means that each leaf is divided into smaller leaflets, which are also divided into even smaller leaflets that are about half an inch long. Although individual leaves are actually quite large, the collective foliage is pleasantly delicate and lacy. This foliage turns yellow early in autumn and disintegrates as it falls, leaving minimal debris to rake. New foliage develops somewhat late in spring, along with inconspicuous flowers.

Shady characters inhabit some of the best gardens. Actually, most of the best gardens have some sort of shade tree. There are so many to choose from for every sort of garden. Some stay small and compact enough to provide only a minimal shadow for a small atrium. Others are large enough to shade large areas of lawn.

Like every other plant in the garden, shade trees should be selected according to their appropriateness to particular applications. Favorite trees are of course welcome, but should be placed in appropriate locations where they will be less likely to cause problems later. For example, those of us who like silver maples should only plant them where they will not crowd other trees, and if there is sufficient area to accommodate them when mature. Southern magnolias are bold shade trees, but create too much mess for infrequently raked lawns, and create too much shade for many other plants around them.

Shade trees near to the home should be deciduous if possible. This means that they will drop their leaves to be not so shady when it would be good to get more sunlight through winter. Honey locust, red oak, Raywood ash, tulip tree and many varieties of maple (except Japanese maple) are some of the best. Silver maple gets a bit too large for small gardens, but is an elegant shade tree for large lawns. Japanese maple and smoke tree are small trees that fit nicely into an atrium or a small enclosed garden.

Evergreen trees also make good shade trees, but should be kept farther from the home if possible, in order to avoid shading too much through winter. Besides, most evergreen trees are messier than deciduous trees so are not so desirable over lawns, patios or roofs. Camphor tree and several of the well behaved eucalypti are delightful shade trees where their litter will not bother anyone. Mayten tree is a smaller tree for more confined areas. Strategically placed evergreen shade trees can also function to obscure unwanted views.

Every shade tree creates a specific flavor of shade. Honey locust makes just enough shade for summer weather without making the garden too dark for other plants and lawn grass. Silver maple is a bit shadier. The shade of redwood and Southern magnolia (when mature) though, is so dark that not many other plants want to get close to them.

Remember that appropriate shade trees may be in the garden for decades or even centuries. It is best to select them accordingly so there will be fewer problems in the future.

Working within landscapes is obviously very different from working on the farm. Actually, there are too many differences to mention. One difference is people. There are only a few on the farm, spread out over many acres. Conversely, the landscapes that I work in are designed for use and enjoyment by countless people who attend events there. I can rarely get away from all of them. Although it can be fun, it can also be challenging, and often interesting. On rare occasion, I find artifacts that make me wonder about whomever left them. This tiny terracotta pot with “Zoey” painted on it, for example, was found in a small landscape outside of a bookstore, quite a distance from the facility a which young children typically engage in such crafts. I hate to think that Zoey misplaced it there. I sort of hope that it was intentionally left there, perhaps containing a tiny plant that Zoey hoped a gardener would find and add to the landscapes. If so, I found it too late and empty. Zoey does not need to know that. Hopefully, if she returns, she finds something that she believes to be her plant growing happily in our landscapes.

Most popular modern petunia are hybrids of two primary species, and a few others. They classify collectively and simply as Petunia X hybrida. Although popular as warm season annuals, some can be short term perennials. They are only uncommon as such because they get shabby through winter. Yet, with a bit of trimming, they can regenerate for spring.

Petunia are impressively diverse. Their floral color range lacks merely a few colors. Also, flowers can exhibit spots, speckles, stripes, blotches, haloes or variegation. Flowers can be quite small, or as broad as four inches. Some are mildly fragrant. Some are quite frilly with double bloom. Cascading types can sprawl three feet while most are more compact.

Petunia are perhaps the most popular warm season annual. They can bloom from spring until frost, though they can get scrawny after a month or so. Trimming of lanky stems can promote more compact growth. Deadheading might promote fuller bloom for some types. Petunia enjoy sunny exposure, regular watering and rich soil. They perform well in pots. Cascading varieties are splendid for hanging pots and high planters.

Planting should not be complicated. The primary objective is to settle formerly contained roots into the ground safely. It includes motivating roots to disperse into surrounding soil. This might involve disruption of constricting or congested roots. It may involve addition of fertilizer. Soil amendment such as compost is likely useful to entice root growth outward.

For almost all substantial woody plants and most large perennials, this is only temporary. Their roots disperse faster than their original soil amendment decomposes. They require no more soil amendment incorporated into their soil afterward. Such incorporation would damage their dispersing roots. This could defeat the original purpose of soil amendment.

For such substantial plants, soil amendment only provides a transition into endemic soil. Without it, roots may be tempted to continue to grow within their original potting medium. If endemic soil is less appealing to them, they might lack motivation to disperse outward. Soil amendment mixed with their endemic soil provides them the motivation they require.

Mulching with soil amendment over the surface of the soil is a different procedure. Since it requires no incorporation into the soil, it severs no roots below the surface. Yet, it helps retain moisture and insulates the soil. As it decomposes, mulch adds organic nutrients to the soil. For established plants, mulching is a noninvasive technique with a few benefits.

Vegetable plants and annuals enjoy soil amendment more than more substantial plants. Proportionately, they consume much more of the nutrients that the amendments provide. Yet, they do not inhabit their soil long enough to crave more than they start with. Addition of amendment during their replacement damages no roots. It provides for the next phase.

Soil amendment is available either bagged or in bulk from nurseries and garden centers. Home garden generated compost is less expensive, since it costs nothing but effort. The process of composting is involved, but it utilizes otherwise useless garden detritus. Many home gardens generate more compost than they may use. Neighbors sometimes share.

Four o’clock has been unusually pretty in bloom. It self sows almost enough to become a weed, but I am fond of it.

1. Mirabilis jalapa, four o’clock blooms in various shades of pink, including one that can be fragrant about 4:00 and into evening. It alternatively can bloom white, red, magenta, yellow, or with striped combinations of colors. Different colors may bloom on one plant.

2. Mirabilis jalapa, four o’clock does not exhibit very much variation of floral color here, though. This yellow bloom is one of only three variations. I thought that I noticed simple red bloom through previous summers, but can find none now. I would like to find white.

3. Mirabilis jalapa, four o’clock demonstrates what can occur when the two other colors here combine. It is the third of only three variations that I am aware of. From a distance, it seems to be peachy orange. Some of its flowers are just like the first two pictures here.

4. Nerium oleander, oleander that blooms pink mingles with the oleander which blooms white that I posted a picture of three weeks ago. Oleander is so cheap and common here that, even with oleander scorch, it is still the primary shrubbery for freeway landscapes.

5. Fuchsia magellanica, fuchsia is easy to miss where it is wedged between healthier and prettier hydrangea and canna. I should grow copies of it elsewhere. It would probably be bigger with fuller foliage where it gets more water than the four o’clock and oleander get.

6. Rosa spp., rose is in a rose garden that is nowhere near the four o’clock, oleander and fuchsia, but is too pretty to omit. I believe that it is ‘Double Delight’. It is nicely fragrant. Flowers bloom white with red edges, but fade to mostly pinkish red, just as they should.

This is the link for Six on Saturday, for anyone else who would like to participate: https://thepropagatorblog.wordpress.com/2017/09/18/six-on-saturday-a-participant-guide/

My niece knows the weird flowers of passion vine as ‘flying saucers’ because they look like something from another planet. The most common species, Passiflora X alatocaerulea, has fragrant, four inch wide flowers with slightly pinkish or lavender shaded white outer petals (and sepals) around deep blue or purple halos that surround the alien looking central flower parts. The three inch long leaves have three blunt lobes, and can sometimes be rather yellowish. The rampant vines can climb more than twenty feet, and become shabby and invasive, but may die to the ground when winter gets cold. Other specie have different flower colors. Some produce interesting fruit. Passiflora edule is actually grown more for its small but richly sweet fruit than for flowers.