The earliest infestations of giant reed, Arundo donax, that clogged tributaries of the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers supposedly grew from pieces used as packing materiel for cargo from China. It was simply dumped into the rivers as cargo was unloaded in port cities like Stockton and Sacramento. How it got to China from its native range in the Mediterranean is unclear.

Because it is so aggressive and invasive, giant reed is almost never found in nurseries. In many rural areas, particularly near waterways, it is listed on the ‘DO NOT PLANT’ list. However, giant reed can sometimes be found in old landscapes where it was planted before it became so unpopular. It can also grow from seed in unexpected places.

Once established, giant reed can be difficult to eradicate or even divide. It spreads by thick rhizomes that resemble the stolons of bamboo, but not quite as tough. It is often mistaken for bamboo. Where it gets enough water, it can get nearly thirty feet tall, with leaves about two feet long.

Where it can be contained and will not become an invasive weed by seeding into surrounding areas, giant reed can provide bold foliage that blows softly in the breeze. ‘Versicolor’ (or ‘Variegata’) has pale yellow or white variegation, and does not get much more than half as tall as the more common green (unvariegated) giant reed. Incidentally, the canes of giant reed are used to make reeds for musical instruments.

The popular wisterias that bloom so profusely before their new foliage appears in spring are Chinese wisteria, Wisteria sinensis. Others specie are rare. The impressively longer floral trusses of Japanese wisteria are not as abundant, and bloom late amongst developing foliage. American and Kentucky wisteria are more docile small vines, but their floral trusses are both short and late.

The popular wisterias that bloom so profusely before their new foliage appears in spring are Chinese wisteria, Wisteria sinensis. Others specie are rare. The impressively longer floral trusses of Japanese wisteria are not as abundant, and bloom late amongst developing foliage. American and Kentucky wisteria are more docile small vines, but their floral trusses are both short and late. Bluegum is famously problematic. It is too big, too invasive, too messy, too structurally deficient, and as demonstrated in the Oakland fire, too combustible. Dwarf bluegum, Eucalyptus globulus ‘Compacta’, is a completely different animal that does not even look related. It gets only about fifty feet tall, with a dense and somewhat symmetrically rounded canopy. The mess and falling limbs do not affect such a large area.

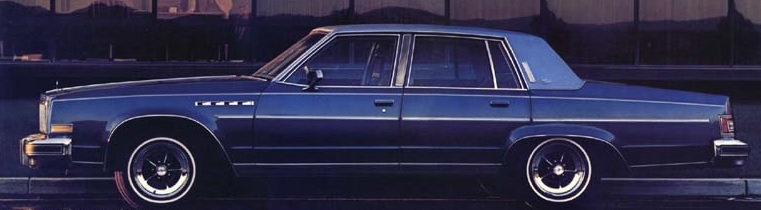

Bluegum is famously problematic. It is too big, too invasive, too messy, too structurally deficient, and as demonstrated in the Oakland fire, too combustible. Dwarf bluegum, Eucalyptus globulus ‘Compacta’, is a completely different animal that does not even look related. It gets only about fifty feet tall, with a dense and somewhat symmetrically rounded canopy. The mess and falling limbs do not affect such a large area. For my exquisite 1979 Electra, planned obsolescence did not work out so well. It was probably a grand Buick for that time, and one of the last with tail fins! It was elegant. It was big. It was steel. It was made to last ten years or 100,000 miles . . . and that was it. Seriously, as much as I enjoyed that car, it did not want go to much farther than it was designed to go. It limped along for almost 20,000 miles more, but was not happy about it, and was really tired and worn out by the time it went to Buick Heaven.

For my exquisite 1979 Electra, planned obsolescence did not work out so well. It was probably a grand Buick for that time, and one of the last with tail fins! It was elegant. It was big. It was steel. It was made to last ten years or 100,000 miles . . . and that was it. Seriously, as much as I enjoyed that car, it did not want go to much farther than it was designed to go. It limped along for almost 20,000 miles more, but was not happy about it, and was really tired and worn out by the time it went to Buick Heaven.